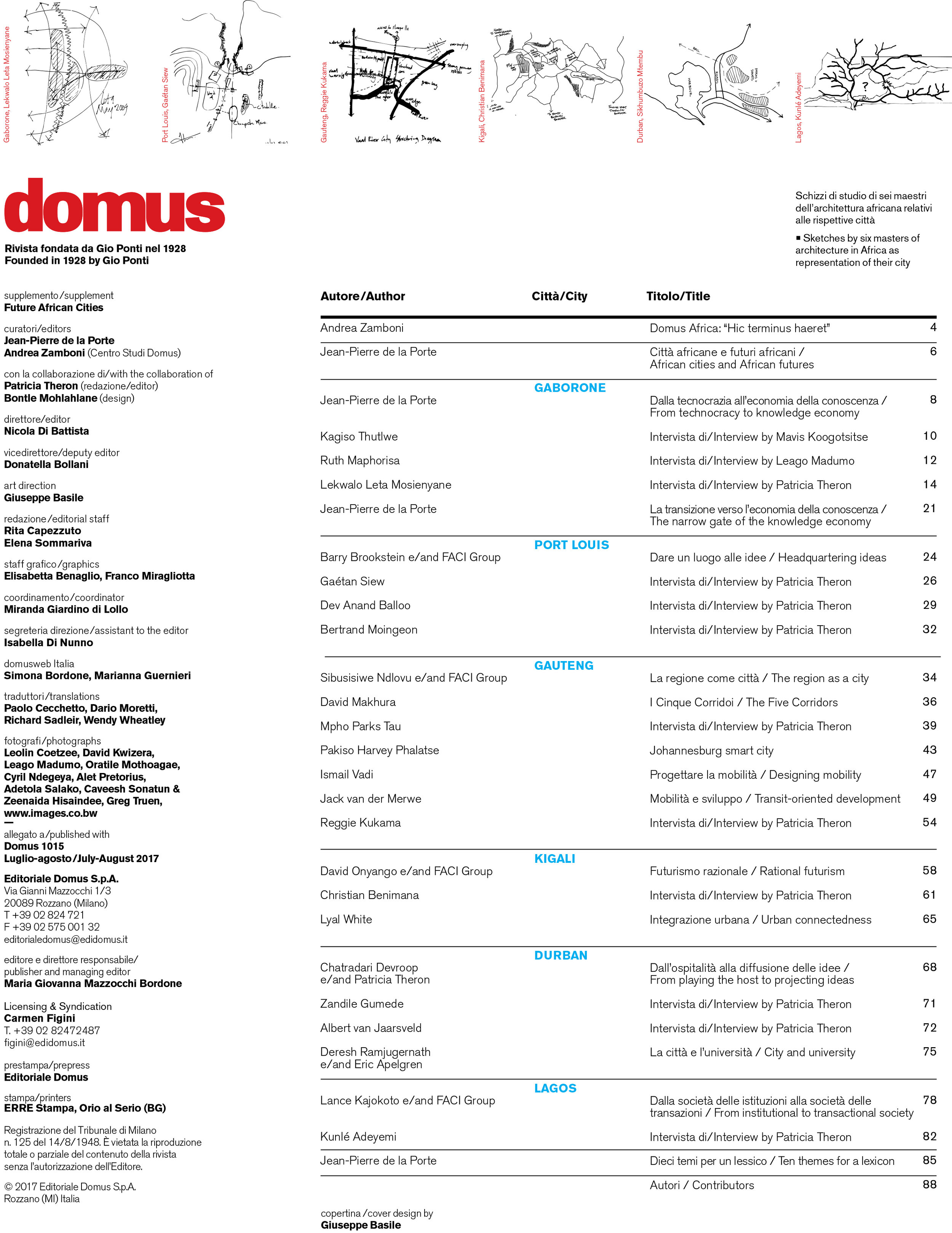

Domus Future African Cities

edited by Jean Pierre de la Porte and Andrea Zamboni

with the collaboration of Patricia Theron and Bontle Mohlahlane

supplement to issue Domus #1015

Editoriale Domus Milano

With texts by: Andrea Zamboni (Centro Studi Domus), Jean-Pierre de la Porte, Kagiso Thutlwe

Ruth Maphorisa, Lekwalo Leta Mosienyane, Barry Brookstein, Gaétan Siew, Dev Anand Balloo, Bertrand Moingeon, Sibusisiwe Ndlovu, David Makhura, Mpho Parks Tau, Pakiso Harvey Phalatse, Ismail Vada, Jack van der Merwe, Reggie Kukama, David Onyango, Christian Benimana, Lyal White, Chatradari Devroop, Patricia Theron, Zandile Gumede, Albert van Jaarsveld, Deresh Ramjugernath, Eric Apelgren, Lance Kajokoto, Kunlé Adeyemi

DOMUS AFRICA HIC TERMINUS HAERET

Andrea Zamboni

In 1969, the year he designed the Black Box TV set for Brionvega, Marco Zanuso left Milan for Lydenburg, South Africa. He was invited by Sidney Press and his wife Victoria to build a home for their family on the Coromandel Estate developed by Mr Press. It was the beginning of the singular story that led to Casa Press (see Domus issue 1015). The house

visibly bears Zanuso’s signature, but given the particularity of the project, it transcends the occasion to represent an eye-opening advancement of the idea of habitation he was pursuing in Italy. The essence of the project is contained in an article he wrote for Domus (August 1942), entitled “When I build my house, I will go to the outskirts of the city and look

for a meadow”. Not Italian outskirts, but a South African veld saw Zanuso’s description take shape in 1975. Its completion was marked with an engraving in the basalt of Casa Press: Hic terminus haeret (“this end is fixed”), a verse from the fourth book of Virgil’s Aeneid. It also evokes the image of a threshold, where “boundaries adhere” between two worlds. Nowadays, architecture students visiting the house see it cocooned in vegetation like a kind of African Taliesin West. They admire the balanced antinomy between workmanship and nature, and how it represents a link of appreciation between Italy and Africa, an exchange of which Zanuso was a pioneer. That idea of habitation is still relevant – it originated on Italian soil, found fresh humus in South Africa, took root, and developed in fertile ways. In Domus issue 1000, Maria Giovanna Mazzocchi writes how she aspires “to restore to Domus its original meaning of ‘home’ – the home of design, architecture, art, urban planning, and all the new dimensions where the organisation of space, the invention of beauty, the investigation of form and the development of crafts are expressed.” Our homes are equipped with windows to let in light and air, but also to provide us with a viewpoint, a frame from which to look out, and a space toward which to look in. Local editions of the magazine allow Domus to maintain open windows in countries around the world. Now we are opening a window toward Africa and from Africa – a viewpoint of the continent through

its cities. This project originates in cultural motivations and affinity: in 2014, during the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale, I happened upon the Domus devotee Jean-Pierre de la Porte, a central figure in the Southern African Development Community who had co-curated that year’s South African pavilion with Lemaseya Khama. Together, we had the ideaof creating an editorial project on Africa. That year, the national pavilions at the Biennale were invited to respond to the theme “Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014”. Africa has absorbed modernisation by the imposition or the hybridization of Western models, first through imperialism and colonialism, and subsequently through decolonisation and new colonization by the East today. As integrities and equilibriums are being shaken, and as interest is turned on and off based on concerns for the enormous resources, a change of perspective is fuelling a renewal. It is crossing Africa and spreading beyond its borders, culminating in instances of cultural colonization in the opposite direction. By turning the lack of unwieldy superstructures connected to 20th century models into an opportunity, and by rising again in its geographic space, Africa can travel down the path of innovation with great leaps. It can move from an economy of exploitation to an economy of sharing and knowledge, while steering clear of the burdens that are making the East and the West implode. The words of Adalberto Libera come to mind as prophetic here. Referring to the cultural changes felt in Italy during the 1960s, he wrote, “Throughout the development of the various civilisations, the air currents are like waves. They ripple, swell and subside over the centuries. Sometimes, civilisations delineate this wave in a very clear way. Other times, the waves heave unevenly on top of one another, making it difficult to distinguish which is

rising and which is falling. We happen to be at a moment when one wave is subsiding and another is forming. The falling wave is the wise one, the cultured one, the one that loves the

past. The rising wave instead is reckless, loves the present and looks toward the future. Here, the distinction can be seen more clearly, and from this vantage point, we can easily distinguish what is dying down from what is valid.” While the 2014 Biennale directed by Rem Koolhaas (“Fundamentals”) absorbed modernity and proclaimed it spent, the 2016 Biennale directed by Alejandro Aravena (“Reporting From the Front”) passed the baton to the outskirts of metropolises, the outskirts of the world. These areas were presented as the incubators of emerging and alternative models. We know of modern architecture built on African ground through several extraordinary architects from the colonial period. We also know what little transpires of African contemporary architecture through buildings erected by non-governmental organisations or multinationals; other constructions are by a handful of architectural protagonists with ties to Africa. The former offer a partial view of Africa. The latter are emblematic figures who have become stereotypes of a way of looking at Africa. Their work celebrates the continent’s spirit, but is a marginal expression of the multifaceted world of models there. Although it inevitably attempts to be so, Africa is not a unitary entity, but a set of countries belonging to different regions and civilisations. Cities will represent the testing ground for planetary questions. Here, these issues are taking on a momentous order of magnitude and priority. Africa is not only a physical place, but also a condition of thought. To paraphrase Peter Smithson, here things need to be ordinary and heroic at the same time. The dimension of phenomena is so great, that the change of scale constitutes a conceptual difference on a global level. Due to exponential urban drift, the dizzying development of African cities is one of the most relevant phenomena. Another is the statistic datum of the low average age of the population and its increasing prevalence of digital natives. The challenge lies in fields where disintermediation makes fertile terrain for the creation of models for the sectors most inclined toward innovation. We have been hoping for a renewal of the system linked to education in design culture and architecture. African cities are where we can find an original road and an effective possibility of action and change, starting from a new awareness of which our magazine can be a channel. Domus can establish a view of Africa in the contemporary world by representing a vantage point from which to take in the surroundings. Hic terminus haeret – Here the boundary lines adhere.